We live in a stressed out society.

With greater pressures to be top performers in terms of productivity in the work place, as parents, as partners or spouses – something usually has to give. I find that one activity that becomes curtailed for many headache sufferers is sleep. “There just aren’t enough hours in the day!” How many times have I heard this statement, or some variation on it, when headache sufferers seek assistance from a neurologist?

Even when headache sufferers are able to achieve eight hours of sleep each night, often the quality is poor. Bedtime is 10PM, with full sleep onset at midnight or 1AM, and then it is time to start the day again at 6AM. Or just as common – a sleep aid medication brings the onset of sleep at 10PM or 11PM, but then at 4AM the person awakens again, fretting over the upcoming demands the new day promises.

I have found that it has become routine for many patients suffering with headaches to write them off, since stress and sleep deprivation so often play significant roles. Perhaps over-the-counter NSAIDs are utilized, and then chronic daily headaches from the overuse of these medications may develop. These may also be discounted, because headaches are present so frequently that pain becomes something to which some grow accustomed.

There is one headache that patients never attempt to explain away though. It it brutal. This headache declares its presence in such a severe, attention-grabbing, dramatic way that it will not allow itself to be ignored by the person suffering from it.

It is known as the thunderclap headache.

As the name suggests, these are unimaginably intense headaches that start very suddenly and with little to no warning, as a clap of thunder might occur quickly after lightning strikes. If a person experiences a headache like this with no prior history of thunderclap headache, a call to 911 (or another emergency service if outside of the United States) is warranted. This headache, until proven otherwise, can occur with subarachnoid hemorrhage, or bleeding in the brain that takes place due to a rupturing/ruptured aneurysm or other abnormal blood vessel.

Emergency medicine providers obtain head CT scans on patients entering the emergency department with complaints consistent with a thunderclap headache. This is taught to medical students as “the worst headache of someone’s life.” CT scans of the brain, while carrying relatively low sensitivity for detecting early ischemic stroke, are quite good at identifying the presence of hemorrhage in the brain. A normal head CT scan and perhaps a lumbar puncture may both be utilized to better exclude that a leaking or ruptured aneurysm in the brain is present. When everything is normal, what then?

The red arrow calls attention to an area of narrowing in the right middle cerebral artery on angiography in a patient with vasoconstriction, or vascular “spasm.” Image source: http://www.radiopaedia.org

Reversible cerebrovascular vasoconstriction syndrome, or RCVS, occurs when arteries within the brain constrict, spasm, or “squeeze,” as I tell patients. When arteries constrict in this way, blood flow can become restricted to areas downstream within the brain. For this reason, there is a risk of ischemic stroke with this syndrome. There is also a risk of hemorrhagic stroke. If the constriction grows severe enough a vessel may rupture. For most patients, though, the syndrome is characterized by the thunderclap headache without stroke. A workup will fail to reveal evidence of an aneurysm or other vascular abnormality, but if imaging of the arteries is performed using catheter angiography, arteries in the brain will appear “kinked,” “narrowed,” or “beaded.” Once symptoms stabilize, if imaging is repeated, the arteries should return to a normal appearance, hence the reversible part of the syndrome. It is only the vascular narrowing that is reversible though. If an ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke has occurred, brain injury is permanent.

Sometimes patients seeking medical care for thunderclap headaches with classic imaging findings for RCVS may be misdiagnosed as having a very rare condition called primary cerebral vasculitis, or primary CNS angiitis. Primary cerebral vasculitis is a condition in which the body’s immune system attacks the arteries of the brain, resulting in stroke. This is treated by suppressing the immune system. I have seen several patients who have been on steroids for presumed cerebral vasculitis, who actually turn out to have RCVS. There is some evidence that steroids may result in worse outcomes for patients with RCVS, so distinguishing between the two entities is very important. The treatment for the two disorders differs greatly.

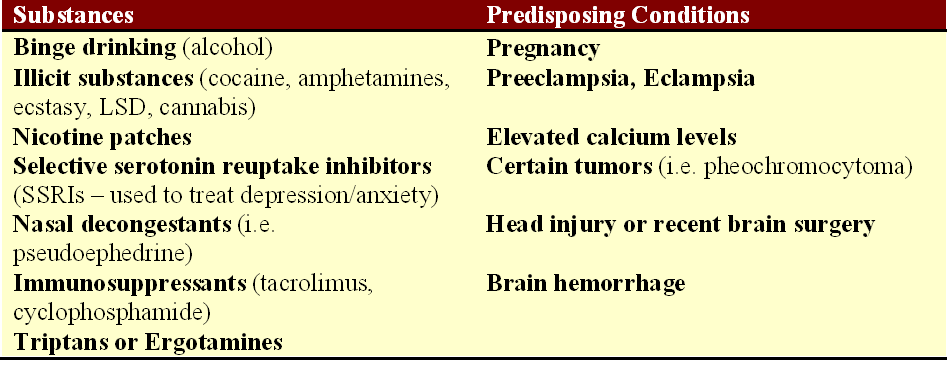

What causes RCVS? The exact cause of RCVS is unknown, but there are predisposing factors that can be associated with RCVS. Pregnancy and the postpartum state, particularly in women with preeclampsia, can be a trigger for the development of the condition. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), frequently used to treat depression and/or anxiety, have also been associated with RCVS. The use of “vasoactive medications,” meaning medicines that can cause constriction of the arteries, can trigger this as well. This would include triptans, ergotamines (such as DHE for migraine), nasal decongestants that contain ephedrine or pseudoephedrine, certain immune suppression medications used in autoimmune disorders or after organ transplantation, or illicit substances such as cocaine, methamphetamine, ecstasy, and LSD. Cannabis has also been reported in association with thunderclap headaches resulting from RCVS.

Identified triggers for the development of reversible cerebrovascular vasoconstriction syndrome. Source: Tan and Flower. Emergency Medicine International, 2012.

Is RCVS a type of migraine? While approximately 40% of patients with RCVS report a history of migraines, thunderclap headaches that occur as part of the vascular constriction are not typical migraines. In fact, triptans that are typically effective in alleviating migraines can actually worsen the narrowing in the blood vessels that is occurring as part of the RCVS thunderclap headaches and should be avoided.

How is RCVS treated? For many patients, RCVS is a self-limited syndrome, and the headaches will stop after several weeks. However, some patients do experience recurrence or ongoing symptoms that may warrant intervention. The first thing that must be done is to remove the trigger, if known, for what may be causing the blood vessels to spasm. If a patient is taking an SSRI, it should be discontinued. Supportive care and pain management through the period of thunderclap headaches may be enough for some patients. There are no randomized clinical trials to definitively answer the question of how best to treat RCVS, but calcium channel blockers (nimodipine, nicardipine, and verapamil are three such examples from this class) have been utilized with some success in the observational studies that are published. Magnesium may be helpful also, particularly in a pregnant or postpartum patient with eclampsia or preeclampsia.

I have seen this syndrome described as “rare,” but like so many syndromes that may result in stroke in younger patients, I ask myself – rare? Or underdiagnosed? I suspect the latter.